My short tribute to Warren Buffett: Q225 letter to partners

Dear partners,

Year-to-date as of June 30 2025, Stone Sentinel Capital (“SSC”) made 38.0% while the S&P 500 Index (“S&P”) gained 6.2%. Figures are gross returns in US dollars. Year-to-date returns are not annualized.

Your manager cringes at reporting quarterly returns and believes that performance is best judged on the basis of rolling 3-5 years. Readers may calculate quarterly returns from figures disclosed in current and previous letters.

As much as excess returns ought to be celebrated, returns over short time horizons say little of your manager.

Security prices almost always reflect the intrinsic values of underlying companies over a long time horizon. But when judged near-term, prices also account for the actions of market participants who pay insufficient attention to fundamentals.

Prices over the short run are often poor indicators of intrinsic values of their underlying. Similarly, returns over the short-run also reflect little of your manager’s ability.

Your manager hopes to shine over the long run during which intrinsic values of selected securities will be reflected in prices.

O Captain! My captain!

Warren Buffett announced that he would step down as CEO of Berkshire Hathaway at the end of 2025.

His announcement capped a 60-year run since he took control of Berkshire, where he oversaw a mind-blowing 5.5 million percent return of Berkshire stock. Every dollar invested in Berkshire in 1965 is worth $550,000 in 2024.

There is no other value investor more forthright, generous, sincere, witty, and wise than Buffett. Your manager has not learned more from another investor.

Your manager hopes to pay tribute by highlighting a few favorite quotes from Buffett.

Thank you, Mr Buffett

What were you doing when you were 20 years old?

The majority of readers were likely in college. Your manager, however, was about to complete mandatory military service and just preparing to attend college.

In 1950, when Buffett was 20 years old, he attended Columbia University to study under Benjamin Graham.

Buffett also visited the headquarters of GEICO in Washington, D.C. and met Lorimer Davidson, an executive who would become CEO. The meeting led to a conversation in which Buffett said he “probably learned more … than [what he] learned in college”.

The value of GEICO was obvious to Buffett. It sold insurance direct to customers, bypassing agents to reduce expenses. It underwrote low-risk customers in the form of government employees with stable paychecks.

More significantly, Buffett stood his ground when leading insurance analysts rebuffed his assessment of GEICO. In Buffett’s words:

“When I first visited GEICO in January of 1951, ... I subsequently went down to Blythe and Company and, actually, to one other firm that was a leading analyst in insurance [Geyer & Co.] And, you know, I thought I’d discovered this wonderful thing and I’d see what these great investment houses that specialized in insurance stocks said. And they said I didn’t know what I

was talking about. You know, they — it wasn’t of any interest to them.

You’ve got to learn what you know and what you don’t know. Within the arena of what you know, ... you have to pursue it very vigorously and act on it when you find it.

And you can’t look around for people to agree with you. You can’t look around for people to even know what you’re talking about. You know, you have to think for yourself. And if you do, you’ll find things.”

Few adults, lest 20-year-olds, can be intellectually independent when authority contradicts them and when few to no peers agree.

Buffett illustrated how successful investors behave:

You don’t need everyone to agree with you to be right.

You don’t have to be old to be right.

The investor is right because his facts and analysis are right, not because of age or social conventions.

That the right logic eventually pays is an intellectual puzzle so rewarding that it inspired your manager to pursue investing.

Buffett did not stop here in his giving. His public writings and conversations influenced your manager’s research process.

Picking stocks is like finding the proverbial undiscovered treasure.

Favorable stocks are rare like gold. Most stocks are average like rocks.

An obvious way to start finding treasure is to know how gold looks like.

However, unlike the metal, favorable stocks often do not stand out as much. The investor who only knows about gold may be hard-pressed to find it.

Another way to find gold is to follow Buffett’s advice, that is to know how rocks look.

When you know how rocks look in the stock market, gold should stand out quickly:

“If you sort of have in your head how all of that looks in different industries and different businesses, then you’ve got a backdrop against which to measure ... [when Charlie and I] read about one business, we’re always thinking of it against a screen of dozens of businesses — it’s just sort of automatic.”

“I can’t be an intelligent owner of a business unless I know what all the other businesses in that industry are doing. ”

“Read everything in sight. [If] you’re reading a few hundred annual reports a year and you’ve read Graham, and Fisher, and a few things, you’ll soon see whether [the stock] falls into place or not.”

In contrast to most investors who scrutinizes projections made by industry experts and company management, Buffett famously pays little attention to their estimates of the vague future.

What he spends time on is the reading of the concrete past dating as far back in history as possible.

History is a key input to Buffett’s assessment of certainty:

“I like a lot of historical background on things ... as to how the business has evolved over time, and what’s been permanent and what hasn’t been permanent, and all of that.”

With deep comprehension of business models and their histories, Buffett can often tell within minutes whether an investment is worth more than an initial glance.

Buffett does not waste any time on marginal ideas. He reserves his deepest thinking for the best ideas:

“The general premise of why you’re interested in something should be 80 percent of it or thereabouts. I mean, you don’t want to be chasing down every idea that way, so you should have a strong presumption.”

The late Charlie Munger said that Buffett “lives one of the most rational lives [he had] ever seen. And it’s almost unbelievable”.

Buffett excels at pursuing what truly counts.

In investing, what truly counts is thinking right.

To think right is also to think for yourself:

“You don’t get paid for activity, you only get paid for being right.”

“The idea of asking investment bankers or somebody to evaluate the businesses you’re going to buy, I mean, that strikes us as idiocy. If you don’t know enough about a business to decide whether to buy it yourself, you’d better forget it.”

While being rational is an obvious goal, it is not easy to be so in investing.

We are conditioned to equate effort with results - study to get good grades, exercise to improve health, do what your boss wants to earn recognition.

Yet in investing, the days and weeks spent in research may amount to nothing, or worse, to a loss when judgment is mistaken.

Effort informs judgment but is not a substitute for it.

This is one of many examples in investing that contradicts what we are conditioned for.

Your manager perceives Buffett as “deeply rational” . He displays a level of rationality that goes beyond what most of the world is conditioned for.

In an example of deep rationality, Buffett practices an uncomfortable but effective way to refine or refute his thesis:

“One of the things [Charles] Darwin did was that whenever he found anything that contradicted some previous belief, he knew that he had to write it down almost immediately because he felt that the human mind was conditioned, so conditioned to reject contradictory evidence, that unless he got it down in black and white very quickly his mind would simply push it out of existence.”

Most of us see the world as we are. And seek confirming evidence to keep views static.

Investors have to see the world as it is. And should seek disconfirming evidence (as Darwin suggested) to adjust views when mistaken.

The former is more comfortable but likely produces the wrong judgment. The latter is more laborious and painful but likely produces the right judgment.

Buffett seems to have mastered the best of both worlds. He takes comfort in the uncomfortable that leads to him judging right, a contradiction itself.

Perhaps it is consistent effort that reduces the labor and pain necessary for the right judgment. However, your manager is not certain that hard work alone can negate the human condition to avoid labor and pain.

The deep rationality of Buffett’s nature is perhaps the cornerstone of his wiring as one of the greatest investors in modern history.

In your manager’s view, no other great investor has written, spoken, and shared more meaningful education, advice, and experiences about investing.

While Buffett retires as CEO of Berkshire, the sun that is his impact on investing and the world will never set.

Thank you, Mr Buffett.

Your manager has read and reflected on Buffett’s writings and conversations more times than he can count.

Knowing is not understanding. Knowing Buffett’s words is not the same as understanding them.

Every reading of Buffett’s words appears to result in a slightly deeper understanding of his principles. Your manager assures you that no time is wasted in the repetitive reading and reflections on his words.

How to know what others do not

In business school, your manager knew a fellow student who exhibited nearly every conventional quality to succeed in investing or any career of his choosing.

Intelligent, diligent, sociable, eloquent, excellent grades, widely recognizable employers on his resume.

A rock star in Wall Street parlance.

Trouble was how he learned.

He never wanted to read an entire book. All he wanted were the key points.

He used to say the CliffNotes version was enough.

On paper he was a major success. He studied enough to get excellent grades. He learned enough to please employers.

Meeting the benchmarks of academic examinations and professional peers ensures he knows what others need him to know.

Yet in investing, if you know what everyone else knows, you can’t be surprised to get what everyone else gets.

Certainly not a recipe for excess performance.

A better solution is to know what others do not.

Your manager chanced upon a quote from a Japanese anime that suggests how:

“If you want to learn something, the only way is to think deeply and go through the pain of uncertainty and frustration.”

Knowing is easy. Understanding is hard because it requires thinking about the implications of knowledge.

In the Four Causes that Aristotle used to explain nature, the Final Cause asks about the purpose and goal of the observed to understand how it connects to everything else.

When the Final Cause is answered, knowledge transcends to insight.

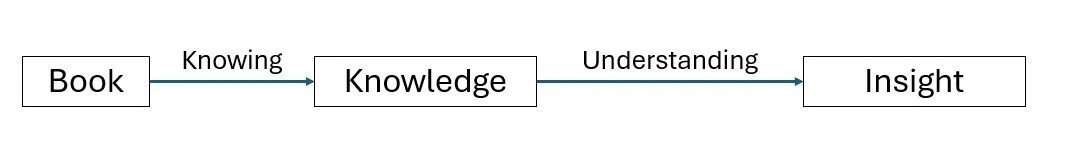

Your manager thinks about the process as such:

A more accurate picture looks like this:

Understanding is “thinking deeply and going through the pain of uncertainty and frustration”, like what Ryu Sasakura described.

But the rewards are significant.

Understanding engenders lesser-known insights on which excess returns in investing depend.

Understanding also ensures that the knowledge and insights are better remembered. They can easily be retrieved from memory and applied at will.

Knowledge and insights can only compound when they are remembered.

For your manager’s classmate to know only the highlights is like going through so little of the journey that he gains neither knowledge nor insight.

Your manager wonders how much of these highlights his classmate can recall.

Portfolio report

Grupo Empresarial San José (GSJ), Claranova (CLA), and Finvolution (FINV) contributed to returns. SSC is currently invested in 5 stocks and holds roughly 5% of total assets in cash.

GSJ is priced at roughly €400m with about €350m of cash net of debt and minority interests, implying that the core construction business and undeveloped land are valued at €50m.

The core construction business generated €32m net earnings last year and €14m in the depths of Covid. Free cash flow was €117m and €17m respectively.

Your manager believes that GSJ stock is an incredible bargain even if the undeveloped land is worth next to nothing.

CLA stock has more than doubled year-to-date, rewarding patient shareholders investing alongside activists who are proven investors in technology and are large shareholders themselves.

The sale of a non-core segment reduced debt, leaving CLA with a software publishing segment that generated roughly €26m free cash flow last year.

CLA is priced at roughly €170m including debt, pricing the software publishing segment at 6.5x FCF. This seems cheap for a business that have recurring subscription revenues and potential to further grow revenues and expand margins substantially.

The activists have lived up to their ambitious promises. As long as they continue to own significant stakes, they are unlikely to slow down in turning around CLA.

Patient shareholders riding on their coattails are likely to be further rewarded.

FINV is a recent addition to the portfolio. As a large nonbank lender in China, the fintech company connects small-ticket borrowers to lenders for a fee.

The company generated $326m net income with 19% net margin and 18% ROE (20% normalized) last year. Its near-$400m FCF was at a multi-year record high, resulting in roughly $1.3b cash and investments and zero debt on its balance sheet.

Yet it is priced at only $2.5b, offering ~30% FCF yields when cash and investments are included.

Investors appear to be hesitant in recognizing the value of FINV because of a brutal industry history. The nonbank micro lending industry has been served strict regulations and capital requirements since 2016, ultimately leading to the exit of 95% of participants.

The wipeout of competition has benefitted the survivors, which operate in a oligopoly dominating 80-90% of originations. FINV appears to be the most technologically competent among survivors. Its risk models process much higher volumes and more diverse data than competitors’, and feature automated feedback loops that update models weekly (some in real-time) compared to quarterly at competitors.

FINV seems to be the most agile and ambitious as the first in its industry to expand outside of China.

Investors seem to be gradually recognizing the value of FINV, almost doubling the stock price this year. Your manager believes that FINV has more to offer.

Your manager welcomes questions and comments at mg@stonescap.com.

At your service,

Marcel Gozali